German and Nordic varieties have been in continuous contact since prehistoric times, which, for this part of the world, means the Early Middle Ages. In particular two contact scenarios have had a profound impact on language history: firstly, language contact between Danish and German on the Cimbrian Peninsula, and, secondly, language contact as a result of the Hanseatic presence in Continental Scandinavia.

Danish and German on the Cimbrian Peninsula

Different ethnic groups and languages have always coexisted on the Cimbrian Peninsula (which today is divided territorially between Denmark and Germany). By the end of the first millennium CE, its southern part was inhabited by Saxons (speaking Old Saxon, the predecessor of Modern Low German), Jutes (speaking Old East Nordic varieties that later evolved into the Jutlandic branch of Danish dialects), Frisians (whose language developed into the modern North Frisian dialects), and Obotrites (speaking Polabian, i.e. West Slavic varieties). Subsequent Germanisation of the Slavic-speaking population from the 12th century onwards resulted in a tripartite distribution of the regional languages that, in a way, still holds today, with Danish in the north, German in the south, and Frisian in the west.

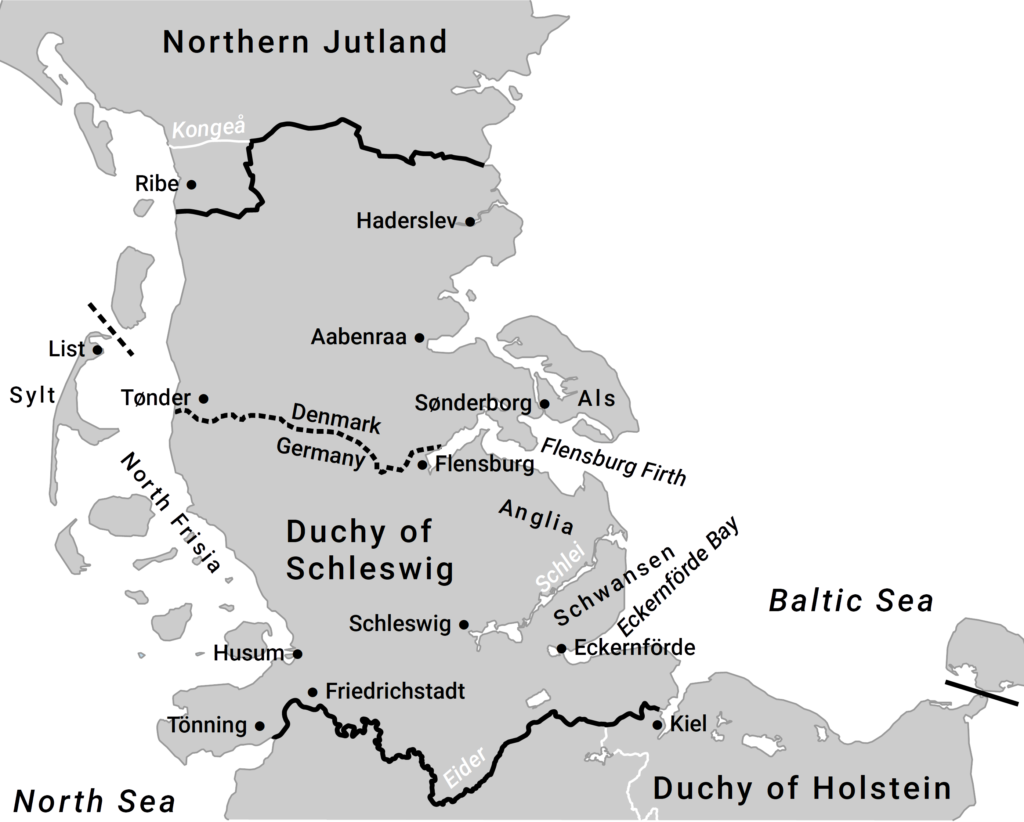

For most of its history, the peninsula was mainly divided politically into three larger territories (as well as some minor polities): Northern Jutland (an integral part of the Danish realm), the Duchy of Schleswig (a Danish fief), and the Duchy of Holstein (a state within the Holy Roman Empire until 1806, later within the German Confederation).

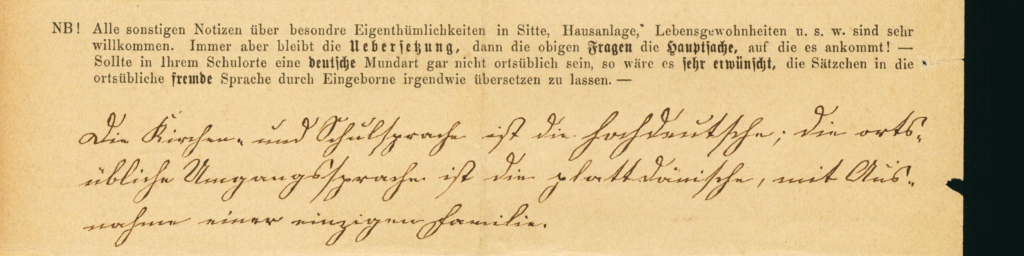

German and Danish (and, to a lesser extent, Frisian) have always coexisted territorially in the Duchy of Schleswig. Until about 1800, Danish was used in everyday communication in rural areas in the northern part (roughly north of a line between Friedrichstadt and Eckernförde), wheras German was used in the south. In addition, German was traditionally used in the towns and among nobility and merchants as well as in the domains of law and administration, including in the northern part. Multilingualism was, in some form and to some extent at least, the rule rather than the exception both at the collective and at the individual level.

The 19th century saw an accelerating shift from Danish to (Low) German dialects in the southern part of the duchy, starting in the eastern regions and proceeding westward. (The Schwansen peninsula had shifted to German by about 1780, and by 1850 the shift had been completed in Anglia.) At the same time, increasing political tensions led to the Second Schleswig War and, eventually, resulted in the annexation of the duchies by Prussia in 1866. After World War I and a subsequent referendum, the former duchy of Schleswig was divided between Denmark and Germany in 1920. However, there is still a Danish minority south of today’s border as well as a German minority in the northern part.

After almost a millennium of intense language contact (involving different and changing contact scenarios over the centuries), nonstandard varieties in the German-Danish contact zone have influenced each other to a high degree, including traditional dialects (Schleswig Low German, South Jutlandic), regional dialects (e.g. regional varieties of High German), and minority varieties (South Schleswig Danish, North Schleswig German). Contact-induced innovations have also spread further north and south, i.e. into more distant Low German-speaking and Jutlandic-speaking areas.

The Hanseatic presence in Continental Scandinavia

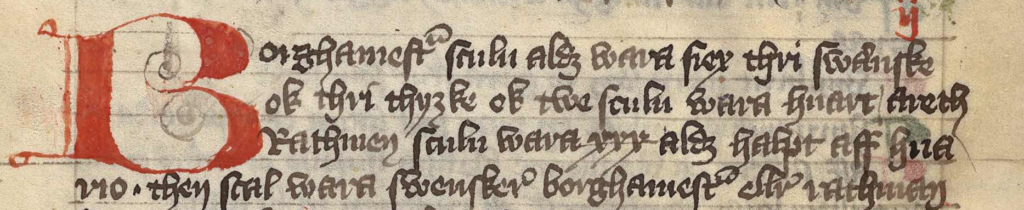

The Hanseatic League was a commercial (and military) confederation of major towns in Northern Germany and neighbouring countries (including free cities, such as Hamburg, Lübeck and Cologne, as well as cities that belonged to other territories, such as Wismar in Mecklenburg or Riga in present Latvia) that dominated trade in Northwestern Europe from the 13th until the 16th century. Low German served as the lingua franca and de facto official language of the Hanseatic League.

Most importantly, the Hanseatic League controlled the maritime trade routes across the North and Baltic Seas and established trading posts and merchant settlements abroad, including in all major coastal towns in Scandinavia (Bryggen in Bergen is the most famous example).

This led to a considerable immigration flow into Continental Scandinavia, with ethnic Germans becoming a large minority (sometimes even a majority) in Scandinavian towns, where they formed an important part of the emerging political, economic, and cultural elite. This included not only merchants, but also craftsmen, miners, and other specialized workers. Social parameters differed across countries and towns. While contact between the different population groups was heavily restricted in some places (e.g. in Bergen), Germans were allowed to integrate more easily into the majority societies elsewhere. In either case, the Hanseatic presence in Scandinavia resulted in long-term, intense language contact between Low German and Continental Scandinavian languages, ranging from initial semicommunication to more developed forms of receptive multilingualism, L2 acquisition, and full-fledged bilingualism.

The Hanseatic presence in Scandinavia did not end abruptly when the Hanseatic League ceased to exist. German companies continued their operations in the Nordic countries, and German influence remained strong over the centuries. In addition, German had an impact as the language of the Lutheran Reformation and in other cultural domains (e.g. science, literature, education) well into the 20th century.

Nordic varieties have been affected by the contact with German to various degrees. Evidence for regional differences can still be found in traditional dialects. Varieties originally used in coastal, urban, and southern areas (including most standard varieties except Norwegian Nynorsk) have been influenced more strongly than inland, rural, and northern areas (the ‘periphery’). Also, Continental Scandinavian varieties show much more traces of German influence than Insular Nordic varieties, where indirect contact with German (via Danish) has been more important.