GrammArNord builds upon a conceptual model of linguistic areality that also serves as the basis for the digital model that is being developed. Areality is conceptualized in terms of elements as well as hierarchical (vertical) and non-hierarchical (horizontal) relations between those elements.

Languoids

GrammArNord deals with a range of entities that are traditionally (and rather inconsistently) classified as traditional/regional/social dialects, registers, dialect groups, standard varieties, languages, language families or branches of language families – and sometimes there is no consensus about their status. Is Elfdalian a language or a Swedish dialect? Is Low German a language of its own or a group of German dialects? What is the status of Nordic, West Nordic, or Continental Scandinavian – are these genealogical or merely typological labels? While it may make sense in certain circumstances to define and debate such questions, GrammArNord follows a more practical approach (inspired by, among others, Cysouw & Good’s [2013] work) in referring to all of these entities as languoids.

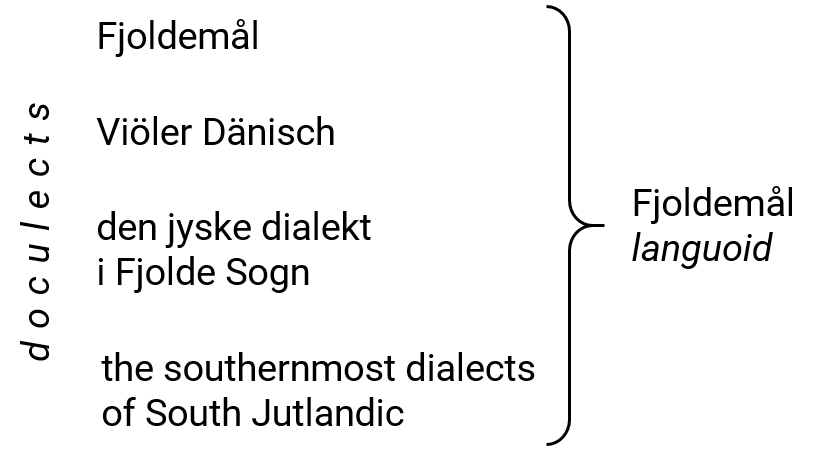

GrammArNord draws on documentary resources that describe (parts of) the grammar of some linguistic entity. In technical terms, a variety as documented in a particular resource is called a doculect. This could, for example, be

- a dialect, as with Bjerrum & Bjerrum’s (1974) Ordbog over Fjoldemålet [dictionary of Fjoldemål], which contains a grammatical description of the traditional (now extinct) dialect of Danish spoken around the village of Viöl;

- a group of standard varieties of a language, as with Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo’s (1997) Norsk referansegrammatikk [Norwegian reference grammar], which describes the Norwegian standard varieties Bokmål and Nynorsk;

- a genealogical group of languages, such as the Nordic languages.

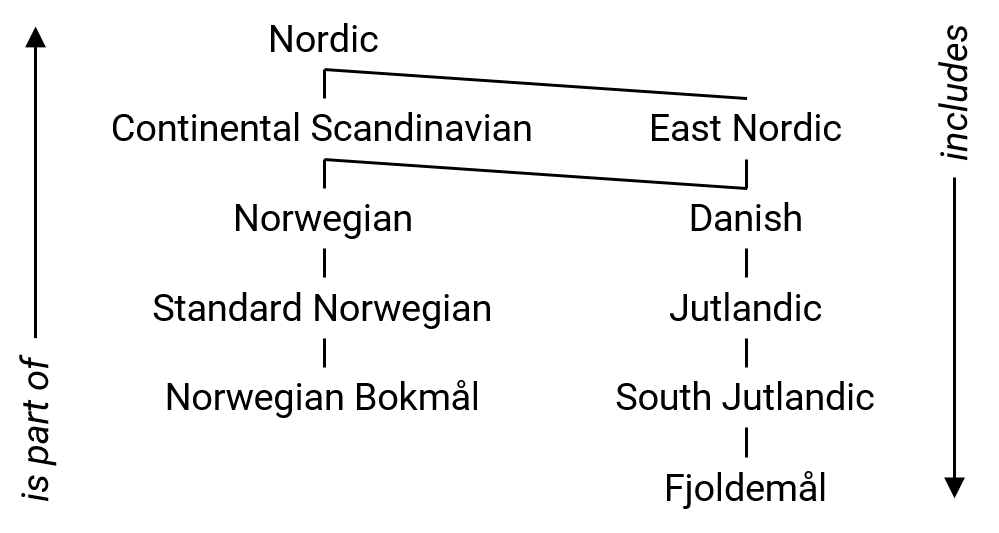

Different doculects may be judged to represent the same linguistic entity, i.e. the same languoid, even if they do not use the same name (glottonyms). In particular non-standard varieties often go by different names in different publications. For instance, Nordic is judged to be the same as North Germanic or Scandinavian. Likewise, Bjerrum & Bjerrum’s Fjoldemål is arguably identical to the doculect that other publications call, say, Viöler Dänisch [Viöl Danish], den jyske dialekt i Fjolde Sogn [the Jutlandic dialect in Viöl Parish], or the southernmost dialects of South Jutlandic. Hence, all of these glottonyms and doculects are assigned to the same languoid.

Languoids are thus defined as (potentially hierarchical) language-like objects that are described in terms of at least one doculect. Nordic, Norwegian, Standard Norwegian, and Norwegian Bokmål are all languoids – and part of a languoid hierarchy that, at different levels, also includes Continental Scandinavian, East Nordic, Danish, Jutlandic, South Jutlandic, and Fjoldemål.

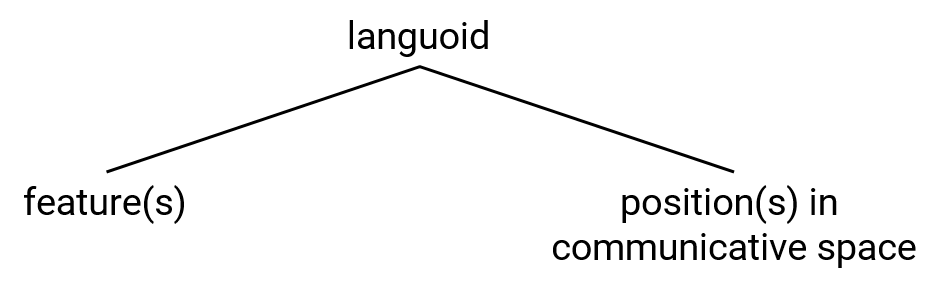

For the purposes of GrammArNord, languoids are abstract entities, i.e. linguistic systems that can be described in a grammar. As such, languoids can be said to have or lack particular structural features and to potentially occupy one or more particular positions in communicative space. Languoids are, however, not defined by their position in communicative space. Standard Danish, for example, is defined by the doculects described in reference grammars and similar works, but it is not defined by the fact that it is used in Denmark in formal or written communication. Instead, this fact is represented by a statement about the languoid’s position in communicative space (along with other such statements, as Standard Danish is also used as an L1 by Danes and others in the Faroe Islands, in Greenland, in South Schleswig, and overseas (e.g. in North America and Argentina), and as an L2 in numerous other places).

References

- Bjerrum, Marie & Anders Bjerrum (eds.). 1974. Ordbog over Fjoldemålet. København: Akademisk Forlag [2 vols.].

- Cysouw, Michael & Jeff Good. 2013. Languoid, doculect and glossonym: Formalizing the notion ‘language’. Language Documentation & Conservation 7, 331–359.

- Faarlund, Jan Terje, Svein Lie & Kjell Ivar Vannebo. 1997. Norsk referansegrammatikk. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Features

A feature can be any structural feature that is defined in a way that makes it possible to determine whether or not it occurs in a given languoid. For example, a languoid is considered to have the

- Definition of

linking possessive word construction

Possession is expressed by an inflected possessive word that agrees with morphological properties of the possessor, the possessum, or both.

Examples come from (but are not limited to) non-standard West Germanic varieties such as Low German as well as from Norwegian Nynorsk:

- Low German

de def ol-e old- sg.f Fru woman (f).sg ehr-en poss.3sg.f-obl.sg.m Wagen car (m).sg - Norwegian Nynorsk

Johan Johan si-tt poss.3.refl-sg.n hus house (n).indef.sg - Norwegian Nynorsk

hus-et house (n)-def.sg.n hans poss.3sg.male.nrefl Johan Johan (male)

Of course, there are differences: In (1), the possessive stem ehr- indicates that the possessor is female, and the suffix -en marks the case, number, and gender of the possessum (oblique, singular, masculine). In (2), the possessive stem si- does not express any morphological property of the possessor, while the suffix -tt marks the possessum’s gender and number (neuter, singular). In (3), the possessive word hans only indicates the possessor’s sex (male). Moreover, (1) and (2) are possessor-initial, whereas (3) is possessor-final.

Such differences are captured by additional features that are defined more restrictively. For example, (1) and (2) are instances of a

- Definition of

possessor-initial linking possessive word construction

There is a possessive construction consisting of (in that order) a possessor noun phrase, a linking possessive word, and a possessum noun phrase. - Definition of

possessor-final linking possessive word construction

There is a possessive construction consisting of (in that order) a possessum noun phrase, a linking possessive word, and a possessor noun phrase.

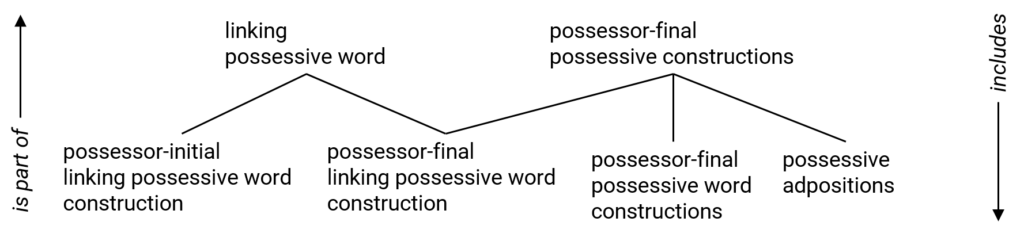

Broad and restrictive features form a hierarchical relation: A languoid with a

Apart from that, the occurrence of a particular feature does not imply anything about other features, whether they are part of the same hierarchy or not. For example, the observation that Norwegian Nynorsk has a

- Norwegian Nynorsk

bok-a book- def.sg.f til to gutt-en boy- def.sg.m

The same feature can also be involved in more than one hierarchy. The Norwegian Nynorsk

-

teori-a-ne theory- pl-def.pl di-ne poss.2sg-pl

Communicative space: places, communities, time, function

Traditionally, areal linguistics is primarily concerned with positions of languoids (and their structural features) in space, which are usually modelled in terms of geographic coordinates (usually points, defined by one pair of coordinates). Variation-sensitive areal typology (Höder 2016, see areal pespective), with its focus on contact effects in neighbouring non-standard varieties, has to adopt a more fine-grained and more nuanced approach.

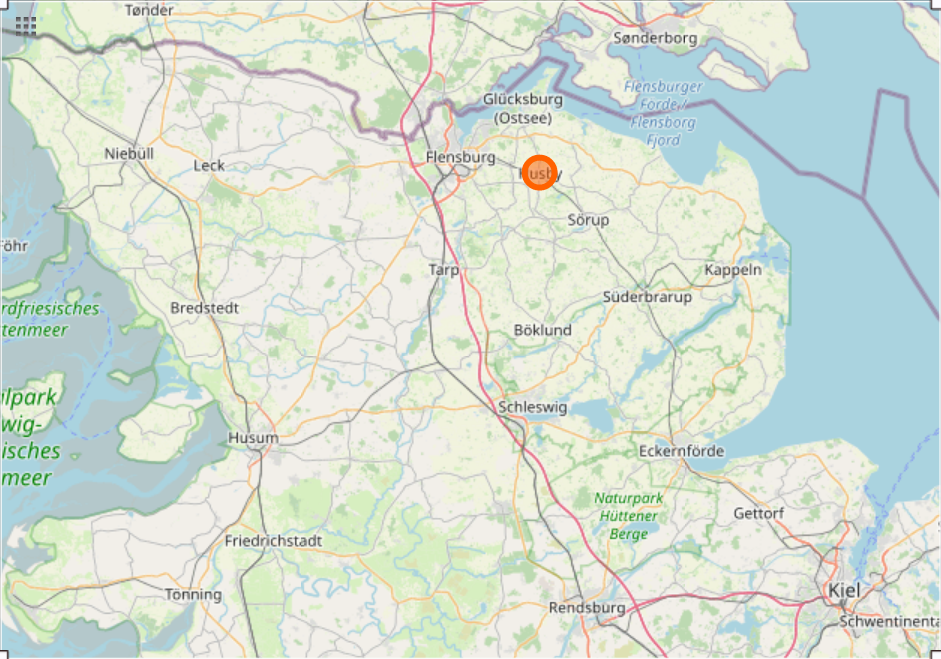

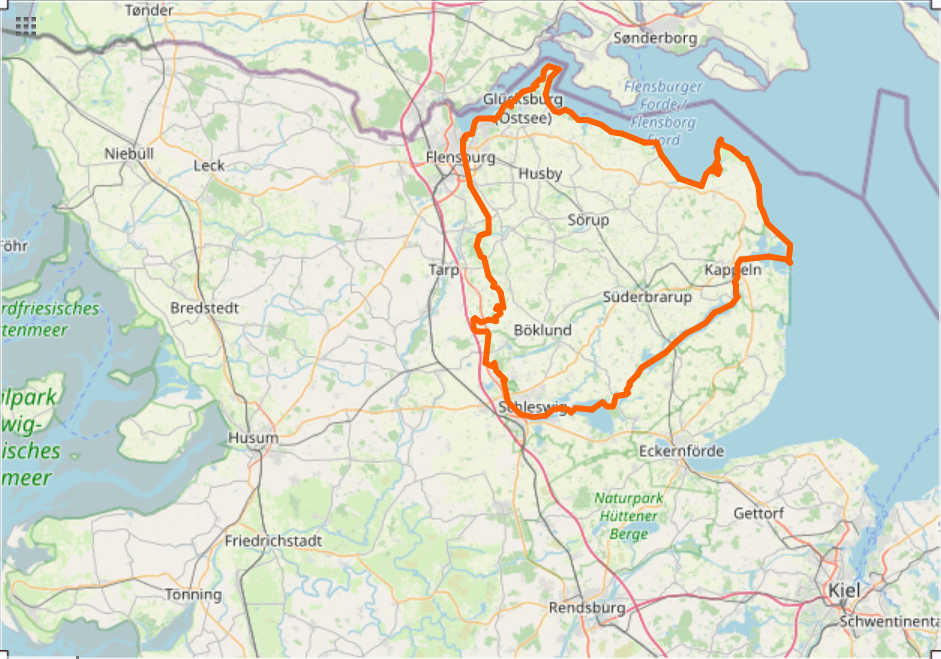

For example, while a traditional dialect (such as the Schleswig Low German dialect of Husby) may be located in a particular village whose location can adequately be described as a point (such as 54° 46′ 0″ N, 9° 34′ 0″ E for Husby), other types of languoids are located in larger regions that have to be modelled as areas, defined by (sets of) polygons, for example the regional dialect of Anglia. This becomes even more obvious at the level of standard varieties such as Standard Danish, which is used in a number of unconnected territories on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, including, but not restricted to, Denmark proper – let alone the level of lingua francas such as English or, in former times, Low German or Latin.

On top of that, a variation-sensitive approach has to take into account the fact that while languoids are defined as abstract entities, their existence in the real world is determined by the communicative settings in which they are spoken: Languoids are not only used in specific places, but also by specific communities during specific periods of time for specific purposes. These parameters are modelled in terms of non-geographic coordinates in communicative space. A member of the Danish minority in South Schleswig may, for example, use five varieties on a daily basis, each with its own coordinates in communicative space:

- Standard German in formal and written communication

- North High German in informal, spoken settings

- (a dialect of) Schleswig Low German with other family members

- Standard Danish in written communication in minority contexts

- South Schleswig Danish in spoken communication in minority contexts

Accordingly, languoids can have different communicative functions (e.g. Standard German is a standard variety, North High German is a regional dialect). Similarly, there are different types of communities (e.g. Standard German is used by the inhabitants of Germany and other countries, hence territorial populations; South Schleswig Danish is used by the Danish minority, an ethno-cultural community), and different types of places (e.g. Husby is a settlement, Anglia is a region).

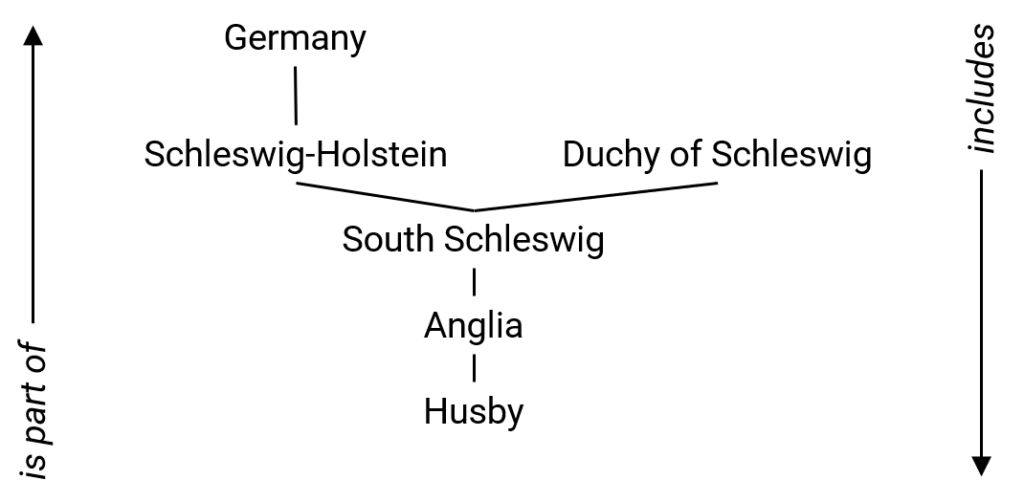

Like languoids, communities and places form hierarchies. For example, Husby belongs to Anglia, which in turn is a part of South Schleswig, Schleswig-Holstein, and Germany. At the same time, South Schleswig also forms part of the (historical) Duchy of Schleswig, the northern part of which is located in present-day Denmark.

Similarly, Finland Swedes (defined as an ethnolinguistic community) are a part of other groups as well, such as Swedes (a broader ethnolinguistic community that also includes, for example, Sweden Swedes) and Finlanders (defined as the population of Finland, also including, among other groups, Finland Finns and Finland Sami).

References

- Höder, Steffen. 2016. Niederdeutsch und Nordeuropa: Eine Annäherung an grammatische Arealität im Norden Europas. Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 139, 103–129.